Timelines

Management Powered by Time.Graphics

Acts of Parliament Powered by Time.Graphics

Feet of Clay? By L. J. Dalby

Readers of "The Wilts & Berks Canal" may have been given the impression that William Dunsford, Manager of that undertaking from 1817 to 1839, was the driving force responsible for what little success it enjoyed prior to the advent of the G.W.R. Some letters from the estate of George Butler of Woolstone near Faringdon, Berks, which have recently been deposited in the Berkshire Record Office throw doubts on whether Dunsford's efforts were always concerned with the well-being of his charge.

Butler, holder of 94 Wilts & Berks shares, whose trade was chiefly centred on Uffington Wharf, dealt in stone for local roads and was the recipient of a number of letters from traders complaining of Dunsford's management. In February 1833 Thomas Vincent of Semington Wharf states that he has been refused permission to examine the Company's books and in April 1836 he writes again complaining of the high charges levied by the Company. He states that Dunsford is too preoccupied with his own stone, coal, salt and slate trade and that it is unjust that he should have control of tonnage rates and arrange these to his own advantage. Vincent affirms that the original brick Priddy's bridge at Vastern which was in excellent condition had been taken down and replaced by a masonry one called Clarendon bridge built with stone supplied by Dunsford. He suggests that Somerset coal traders pay tonnage on returning empty boats but Dunsford's carrying Staffordshire coal do not, nor do his stone boats to the Worcester & Birmingham pay full rates. He suspects that some of these boats are actually Dunsford's property but repaired at Company expense and cites Richard Hodgson of Pewsham Lock House, the Company carpenter as witness to this.

Thomas Short of Abingdon charges Dunsford with selling stone above its real value and with buying timber of poor quality for repairs. He suspects that both Hallet, the Chairman, and Crowdy, the Chief Clerk are implicated with Dunsford and that the Committee of Management has no control over him. He refers to "the monstrous monopoly of Messrs. Dunsford and Company, unfair in principle and unjust in practice". Butler then wrote to the Kennet & Avon Company and in July 1836 received a reply from Sir James Whitley Deans Dundas confirming that Vincent had once been employed by them and that his evidence was trustworthy. The Kennet & Avon books were always available for Shareholder's inspection.

A minute from the Wilts & Berks Committee of 26 January 1837 ordered that the Clerk was to refuse any inspection of the share or minute books as it was the opinion of the meeting that a Proprietor is not warranted in calling for such an inspection. What occurred over the next two years is not known but the Committee changed their minds and at their meeting of 4 April 1839 Dunsford was ordered to meet Butler who had persisted with his request to inspect the books. Dunsford wrote to Butler on 5 April confirming that the books would be available to him. The outcome of the inspection is not recorded; it may be pure coincidence that Dunsford retired in 1839.

The deposited correspondence also contains a letter, dated 27 December 1839, from Edward Leigh Bennet, a Lechlade clergyman, referring to the spring Committee meeting. Before 1838 summer freight had been refused owing to lack of water and for that reason tolls were kept as high as the Act allowed. They would probably have to be reduced later to combat railway competition. Proprietors could expect no further improvements in dividends excepting during an exceptionally rainy summer. A site for a new reservoir was available at Tockenham and this should be built as soon as possible to enable the materials for constructing the railway to be carried. It was expected that the increased carrying possible would pay for the reservoir.

Credit: Railway & Canal Historical Society, Vol 10 (1973) pp 38-9

Dragonfly Boat

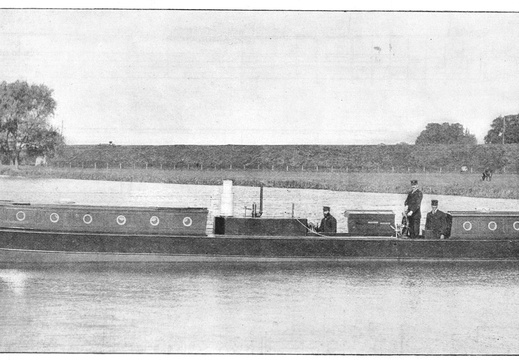

The Wilts & Berks canal magazine ‘Dragonfly’ was named after a boat, here is an extract from magazine issue #1 dated November 1977:

"Our journal is named after the steam inspection launches of HR de Salis, deputy chairman of F.M.C at the time. The second launch had many connections with W & B, being photographed in the locks at Ardington and Latton Basin. It was built at Abingdon in 1895 and its engine boiler built at Wantage"

A set of glass slides held by Swindon Library shows that ‘Dragonfly’ had passed along the Wilts & Berks Canal and North Wilts Canal in 1895, see photos below, these slides feature in Swindon Library’s ‘Flickr Collection, they don’t show ‘Dragonfly’ to the south-west of Swindon, although there is proof that it travelled along the entire canal.

H R de Salis’ book called the ‘Chronology of Inland Navigation’ was published in 1897, and at the back of the book Mr de Salis listed the journeys he had made on the inland waterways, perhaps to show his extensive knowledge. The table shows that ‘Dragonfly’ traversed the Wilts & Berks and North Wilts canals up to three times, as shown in the table below from his ‘Chronology’ book:

Brickmaking

Typical Brick Usage Bridges: Arch 35,000, Lift 15,000 Locks: 178,000 + 425 Cubic feet of stone and 206,000 with a tail bridge Pewsham 3 locks needed 630,000 bricks @import url(https://themes.googleusercontent.com/fonts/css?kit=fpjTOVmNbO4Lz34iLyptLUXza5VhXqVC6o75Eld_V98); ol{margin:0;padding:0} table td,table th{padding:0} .c12{border-right-style:solid;padding:2pt 2pt 2pt 2pt;border-bottom-color:#000000;border-top-width:1pt;border-right-width:1pt;border-left-color:#000000;vertical-align:bottom;border-right-color:#000000;border-left-width:1pt;border-top-style:solid;background-color:#93c47d;border-left-style:solid;border-bottom-width:1pt;width:55.5pt;border-top-color:#000000;border-bottom-style:solid} .c11{border-right-style:solid;padding:2pt 2pt 2pt 2pt;border-bottom-color:#000000;border-top-width:1pt;border-right-width:1pt;border-left-color:#000000;vertical-align:bottom;border-right-color:#000000;border-left-width:1pt;border-top-style:solid;border-left-style:solid;border-bottom-width:1pt;width:132.8pt;border-top-color:#000000;border-bottom-style:solid} .c14{border-right-style:solid;padding:2pt 2pt 2pt 2pt;border-bottom-color:#000000;border-top-width:1pt;border-right-width:0pt;border-left-color:#000000;vertical-align:bottom;border-right-color:#000000;border-left-width:0pt;border-top-style:solid;border-left-style:solid;border-bottom-width:1pt;width:49.5pt;border-top-color:#000000;border-bottom-style:solid} .c2{border-right-style:solid;padding:2pt 2pt 2pt 2pt;border-bottom-color:#000000;border-top-width:1pt;border-right-width:1pt;border-left-color:#000000;vertical-align:bottom;border-right-color:#000000;border-left-width:1pt;border-top-style:solid;border-left-style:solid;border-bottom-width:1pt;width:49.5pt;border-top-color:#000000;border-bottom-style:solid} .c18{border-right-style:solid;padding:2pt 2pt 2pt 2pt;border-bottom-color:#000000;border-top-width:1pt;border-right-width:0pt;border-left-color:#000000;vertical-align:bottom;border-right-color:#000000;border-left-width:0pt;border-top-style:solid;border-left-style:solid;border-bottom-width:1pt;width:41.2pt;border-top-color:#000000;border-bottom-style:solid} .c8{border-right-style:solid;padding:2pt 2pt 2pt 2pt;border-bottom-color:#000000;border-top-width:1pt;border-right-width:0pt;border-left-color:#000000;vertical-align:bottom;border-right-color:#000000;border-left-width:0pt;border-top-style:solid;border-left-style:solid;border-bottom-width:1pt;width:55.5pt;border-top-color:#000000;border-bottom-style:solid} .c22{border-right-style:solid;padding:2pt 2pt 2pt 2pt;border-bottom-color:#000000;border-top-width:1pt;border-right-width:0pt;border-left-color:#000000;vertical-align:bottom;border-right-color:#000000;border-left-width:0pt;border-top-style:solid;border-left-style:solid;border-bottom-width:1pt;width:132.8pt;border-top-color:#000000;border-bottom-style:solid} .c3{border-right-style:solid;padding:2pt 2pt 2pt 2pt;border-bottom-color:#000000;border-top-width:1pt;border-right-width:1pt;border-left-color:#000000;vertical-align:bottom;border-right-color:#000000;border-left-width:1pt;border-top-style:solid;border-left-style:solid;border-bottom-width:1pt;width:41.2pt;border-top-color:#000000;border-bottom-style:solid} .c15{margin-left:18.5pt;padding-top:0pt;text-indent:-0.5pt;padding-bottom:0.2pt;line-height:1.0416666666666667;orphans:2;widows:2;text-align:left;margin-right:7.2pt;height:12pt} .c17{color:#000000;font-weight:400;text-decoration:none;vertical-align:baseline;font-size:1pt;font-family:"Arial 55";font-style:normal}.c0{color:#000000;font-weight:400;text-decoration:none;vertical-align:baseline;font-size:10pt;font-family:"Arial";font-style:normal}.c5{padding-top:0pt;padding-bottom:0pt;line-height:1.15;text-align:left;height:12pt}.c4{padding-top:0pt;padding-bottom:0pt;line-height:1.15;text-align:center} .c20{border-spacing:0;border-collapse:collapse;margin-right:auto}.c6{font-size:10pt;font-family:"Arial";color:#ffffff;font-weight:700}.c1{padding-top:0pt;padding-bottom:0pt;line-height:1.15;text-align:right} .c7{padding-top:0pt;padding-bottom:0pt;line-height:1.15;text-align:left} .c19{background-color:#ffffff;max-width:595.4pt;padding:0pt 0pt 0pt 0pt} .c9{background-color:#4a86e8}.c21{height:27.8pt}.c10{height:15.8pt} .c16{height:16.5pt}.c13{background-color:#93c47d} .title{padding-top:24pt;color:#000000;font-weight:700;font-size:36pt;padding-bottom:6pt;font-family:"Arial 55";line-height:1.0416666666666667;page-break-after:avoid;orphans:2;widows:2;text-align:left} .subtitle{padding-top:18pt;color:#666666;font-size:24pt;padding-bottom:4pt;font-family:"Georgia";line-height:1.0416666666666667;page-break-after:avoid;font-style:italic;orphans:2;widows:2;text-align:left} li{color:#000000;font-size:12pt;font-family:"Arial";text-align:left} p{margin:0;color:#000000;font-size:12pt;font-family:"Arial";text-align:left}

Brickyard

1796

1797

1798

1799

1800

1801

1802

1803

1804

1805

1806

1807

1808

1809

Total

1.Melksham

535,000

179,000

694,750

2.Queenfield & 3.Lacock

523,000

159,750

702,000

4.Pewsham

836,020

235,000

180,250

1,251,270

5.Stanley

656,000

206,000

862,000

6.Cunnegar/ Conigre Farm

380,000

384,000

764,000

7.Foxham

111,000

315,750

556,000

682,400

1,665,150

8.Dauntsey Park

167,200

25,000

30,000

222,200

9.Trow Lane

731,734

741,257

280,000

1,752,991

10.Chippenham

288,050

288,050

11.Dunnington

1,172,750

405,860

23,000

1,601,610

12.Marston

809,151

763,743

1,572,894

13.Longcot

389,077

927,148

1,165,004

2,198,741

1,309,095

5,989,065

Total

2,550,020

1,270,750

1,047,200

581,000

1,444,134

741,257

1,740,800

405,860

832,151

1,152,820

927,148

1,165,004

2,198,741

1,309,095

17,365,980

Contractor

1796

1797

1798

1799

1800

1801

1802

1803

1804

1805

1806

1807

1808

1809

Total

Edwards, Burrows and Foster

1,492,020

1,492,020

John Ching and James Heath

1,058,000

338,750

1,396,750

James Heath

932,000

1,047,200

1,979,200

Samuel Downs

581,000

712,400

1,293,400

McIlquham & Brown

731,734

741,257

1,472,991

Henry Guy

288,050

288,050

James Dobson

1,452,750

405,860

832,151

1,152,820

927,148

1,165,004

2,198,741

1,309,095

9,443,569

Total

2,550,020

1,270,750

1,047,200

581,000

1,444,134

741,257

1,740,800

405,860

832,151

1,152,820

927,148

1,165,004

2,198,741

1,309,095

17,365,980

Source: Wiltshire & Swindon History Centre Ledger A 2424/27 & Ledger B 2424/28 Newspaper Clippings